I caught another new (old) bug. Or is it re-caught? You know how it is. I started

watching a TV series based in the 1700’s, where muzzleloading rifles and pistols are

prominently featured. That reminded me of the fun I had back in the 1990s when I

used to own a muzzleloading rifle.

That muzzleloader was a Thompson/Center Grey Hawk. It was a traditional-style

percussion cap sidelock in .54 caliber. While traditional in format, it was not

traditional in materials. All the metal was silver-finish stainless steel, and the

stock was black plastic.

I took it hunting one year, in the HAM (handgun, archery, and muzzleloader) javelina

season. One day, we finally found the piggies, about 100 yards away across a barb

wire fence. I wore a belt over my hips that held my “possibles” pouch, containing

all the gear that you need to reload a muzzleloader in the field, along with a Ruger

Blackhawk revolver in a holster.

To shimmy under the wire, I removed the gun belt, and made the fateful decision to

leave it, and my daypack behind at the fence to make my final stalk. After all,

what javelina could possibly survive an encounter with a .54 caliber lead ball? A

cottontail that met one of those balls earlier in the hunt was pretty much totally

destroyed.

But I missed. So there I was, standing there holding an empty pipe, while the herd

ran every which way, including right past me! What a helpless feeling that was.

Eventually, I traded that rifle away and had not looked back at muzzleloading firearms

since. In the meantime, muzzleloading technology had advanced in leaps and bounds.

Traditional sidelocks, whether flintlocks or percussion caplocks, had become a very

small percentage of the overall muzzleloading market. Most muzzleloading rifles these

days are inlines, typically sparked by #209 shotshell primers, and fueled by pelletized

black powder substitutes, not loose black powder. Actually, makers of muzzleloaders

today offer a dizzying array of options, in guns, in fuel, in projectiles, and in

ignition. Today’s modern muzzleloaders are capable of outstanding accuracy and reach

that approaches the capabilities of smokeless cartridge firing rifles.

But my fresh interest wasn’t triggered by a desire to hunt with a modern muzzleloader.

While it may be nice to get revenge on the piggies for my earlier failure, it was seeing

all those 18th century flintlocks on the TV series, the English Brown Bess, and the

American Kentucky rifles, that piqued my interest. Since I wanted traditional, but

had no desire to fuss around with a flintlock, I decided to go back to what I knew –

a Thompson/Center percussion cap sidelock.

Of course, T/C is presently making no firearms, let alone traditional sidelock

muzzleloaders, which were discontinued in 2007. After the company was purchased by

S&W, a decision was made to halt all production in 2021.

But there is recent good news. T/C’s tooling, inventory, and intellectual property

was sold this year to Gregg Ritz, the former CEO of the company. Gregg is in the

process of restarting the company, starting with the Encore product line. He does

plan to make traditional sidelock muzzleloaders again, but that is at least two years

out.

T/C was instrumental in getting the sport of muzzleloading kicked off in the modern

era. In 1970, T/C introduced their Hawken rifle. Then, in 1972, the movie “Jeremiah

Johnson” came out, featuring Robert Redford as a mountain man in the early 1800s.

This was quite fortuitous for T/C, as Hawken rifles starred in the movie. T/C

successfully lobbied many state game departments for the creation of special

muzzleloader hunting seasons.

Late 1980’s Thompson/Center New Englander

I had no trouble whatsoever, finding numerous examples of used T/C muzzleloaders on

Gunbroker.com. Of course the best part about buying a muzzleloader on Gunbroker

is that there is no need to put an FFL into the middle of the transaction. A

muzzleloading black powder firearm is not a regulated legally-defined “firearm” subject

to background checks and all that rigamarole. Bid, win, pay, and the rifle is sent

directly to your home.

I found one that looked good to me, a “New Englander” model in .50 caliber. It was

listed for $399, but with the “Take a Shot” option. That meant that I could make an

offer. I “took a shot” at $360, and the offer was immediately accepted. It was so

quick, that it may have been an automatic setting when it was listed.

A lot of sellers on Gunbroker charge you a credit card fee of around 3%, including

this one. On top of that was Arizona state tax. And on top of that was a fixed $40

charge for shipping. All said and done, the purchase cost me just under $450,

delivered.

The New Englander was one of T/C’s most basic traditional muzzleloading rifles.

Nothing fancy, no double-set triggers, no octagonal barrel, no brass patch box. I

guess that its simple functional purity is what appealed to me.

In fact, it is just the walnut and blued metal version of my old Grey Hawk. There was

even a version of the New Englander that used the same plastic stock as the Grey Hawk.

The Grey Hawk had a 24” barrel, where the New Englander has a 26” barrel, both 1-in-48”

twist.

But I knew that buying the gun was only the start of what I would need before I could

take my first shot with the rifle. As I waited for the gun to arrive, I went down to

Sportsman’s Warehouse to purchase as much of the needed accessories as I could. But

they didn’t have everything.

Most critically, they had no #11 percussion caps. I came to learn that percussion

caps have been tough to find in the last 3 years or so. I had no idea. I guess since

modern inline muzzleloaders had taken over the market, most of which use shotshell

primers, the demand, and hence production of percussion caps had plummeted.

What to do? Research led me to a company that makes dies to punch out caps from aluminum soda cans. They

also sell the chemicals to make the priming material.

Another company offers a replacement for the percussion cap nipple that allows you

to use #209 shotshell primers. This solution comes in two parts: First the

replacement nipple that accepts the primer. On to that, another piece screws on

that contains the firing pin that hits the primer when the hammer drops. I ordered

one of these setups.

Since it had been nearly 30 years since my last one, I figured that I needed to get

the original T/C manual, just to make sure that I was reminded about anything that I

might have forgotten. These are available on eBay, in several editions.

An order to Midway USA got me a box of 100 .490 caliber lead balls and 3 boxes of Hornady

Great Plains pre-lubed conical bullets, 20 bullets per box.

Then I needed a box to store all this stuff. MTM makes such a

muzzleloader-specific

box.

Pictured here are a number of the accessories that you might need to shoot or hunt with

a traditional muzzleloader:

Let’s start with the upper left, moving right, then down to the second row. First are

cleaning patches. When target shooting, I found myself swabbing the bore with a wet

patch, then a dry patch after each shot. Otherwise, getting a patched ball down the

bore gets tougher and tougher each time.

Next is a small spray bottle of “Moose Milk”, a popular black powder solvent. This is

what I used to dampen the wet swab patches between shots to keep the bore clean.

Finishing the top row is the box of .490” lead balls and one of the boxes of the Hornady

Great Plains bullets. Because you seat a lead ball on top of a lubed patch (shown below

the Great Plains bullets), the balls need to be slightly undersized from bore diameter.

The lubed patch takes up the difference and engages the rifling.

The Great Plains bullets have a slightly undersized and hollow base to allow starting a

bullet down the bore, but the upper driving band is full bore diameter to engage the

rifling. No patch is required, but savvy shooters often use a lubricated felt disc wad

under the bullet, over the powder, to protect the pure lead base from the hot gas. I

haven’t tried that yet.

Proceeding to the bottom row, left, is a one pound canister of Pyrodex RS black powder

substitute. Back in my Grey Hawk days, I also only ever used Pyrodex. The RS stands

for rifle and shotgun. This is equivalent to the FFg (“2F”) grade of black powder.

These days, there are several additional new BP substitutes out there, but they may not

ignite well with percussion caps. They may need the hotter spark of #209 primers.

Again, I was going with what I already knew and was comfortable with.

To the right of the powder is an original T/C short starter. This was another eBay find,

new, unused in original packaging. You can see how it is used to start a patched ball

down the bore in the sequence of pictures below.

To the right of the ball starter is a capper. Those percussion caps are tiny little

things, difficult to handle. The capper is basically a magazine for percussion caps

that make it easier to place a cap onto the nipple. I’m not happy with this particular

one. It doesn’t hold the cap at the end very tightly and they tend to fall off, which

negates the entire point of it. I’ll be looking for something better.

The green tubular things are muzzleloading speed loaders. The cap at one end is labeled

“powder” and the cap at the other end is labeled “ball”. You place a patched ball (or

conical bullet) into the end labeled “ball” as if you were starting the projectile down

the muzzle. Close the cap. Then in the end labeled powder, you drop your measured powder

charge. Then cap that end.

These make it faster to reload your rifle in the field. Open the powder end and pour

the powder down the muzzle. Open the ball-end cap, hold the speed loader over the muzzle

and push the ball down through the speed loader into the muzzle using your ball starter.

Use your ram rod as normal to get the ball or bullet all the way down to the breech end

of the barrel.

Pictured below the speed loaders is a field flask for powder. The mountain men used a

powder horn, but a hunter today doesn’t need to carry that much powder in the field.

This brass flask only holds enough powder for maybe 10 shots. That’s more than enough,

especially if you are carrying speed loaders with pre-measured charges.

In the round white tin below the lead balls, to the right of the speed loaders, are #11

percussion caps. Yes, I found some, but not in any store, nor online. At a recent club

shoot I mentioned to Wade that I was getting back into muzzleloading, but that I couldn’t

find percussion caps anywhere. It turned out that he had a stock of them. I happened to

have a pistol scope that he could use, so we struck a deal that resulted in the pistol

scope going to him, and some dollars and some percussion caps coming to me.

Below the tin of caps is a 3-in-1 combination tool. One end is a small hammer that

allows the barrel wedge to be started out. Another end has a claw-fork to pull the

barrel wedge all the way out. The barrel wedge is what holds the barrel into the stock.

Removing the barrel from the stock is important for a thorough cleaning, which I will

explain shortly. The third end of the combo tool is a nipple wrench to allow the removal

of the nipple from the barrel.

Next is an adjustable brass powder measure. You may know that black powder and its

substitutes are measured volumetrically, not actually by weight. This powder measure

adjusts to measure from 30 grains to 120 grains in 10 grain increments. A typical

charge for this rifle is from 70 grains to maybe 100 grains.

Finally, there are the pre-lubed patches used for shooting lead balls, already mentioned.

By the way, a .50 caliber lead ball weighs about 177 grains. The Hornady Great Plains

bullets weigh 385 grains, more than twice what the lead balls weigh.

Loading procedure: 1. Measure powder, drop down bore. 2. Place ball over pre-lubed patch

over the muzzle.

3. Using the stubby nub of the short starter, seat patched ball down

bore. 4. Using longer side of the short starter, push ball down about 4 or 5 inches.

5. (not shown) Push the ball all the way down using ram rod, seating firmly on top of

powder. 6. Place cap on nipple.

Right now I don’t have any kind of a pouch for carrying supplies in the field for

hunting. I plan on making myself some kind of a leather pouch, but probably not a

purse style one that hangs over the shoulder as one pictures the mountain men of old

using. I’m leaning toward a belt pouch, though I might add some D-rings to give me

the option of attaching a shoulder strap if I later decide that’s what I want to do.

When the rifle finally arrived at my doorstep, it came through the U.S. Postal

Service by the way, I found that it was in great shape - looked practically new.

Then I ran some cleaning patches down the bore. They came out blackened. Uh oh.

Somebody shot the gun then neglected to clean it before putting it away – a cardinal

sin when it comes to black powder firearms. How long ago was that? Also, the rifle

came from a moister place than the desert southwest – Georgia.

It didn’t take too many more solvent soaked patches before they started coming out

clean, but then I shined a strong flashlight down the bore and saw ugliness. Not

good.

I hold out hope though. I have some old military surplus rifles with rough bores

that still shoot acceptably. Such are the risks when you decide to buy an

approximately 35 year old black powder gun I suppose. I had hoped that since the

outside looked well taken care of, that the inside would have been as well.

The first chance I had to shoot the New Englander was at the July 20th Combo

Silhouette Match. I brought it out to show it off and of course to get first shots

down range.

I took the first shot, then three other club members gave it a try. We shot patched

round balls at the big pigs at 100 meters. None of us hit a piggy. It seemed that

the sights were set to hit too high, and a bit rightward.

About a week later I decided to go up to the high country to put the rifle on paper

to sight it in and to check grouping. I took my camper and stayed for a couple of

nights. I spent most of a day shooting this rifle and getting re-acquainted with

shooting a muzzleloader.

The first thing I tried to do was get velocities. I set up the LabRadar, but was

not getting good results. Was the big cloud of smoke interfering with the radar

signal? I only tried a few shots before giving up. I might give it another try

the next time.

I shot patched round balls (PRB) for most of the day, chasing zero on the rear sight.

For PRB, I ended up cranking the sight all the way down. In the end, it was a bit

frustrating, as grouping sucked. Just when I thought I had it zeroed, I would get a

flyer way off to the side, or the next several shots moved way over.

I was shooting at a round black bullseye target, 8 inches in diameter, at ranges

between 65 and 85 yards. My modest goal was to get them centered in the black and

keep them there, but that wasn’t happening.

I tested with various charge levels from 70 grains to 90 grains, even testing the 5

grain increments between the notches on the powder measure. None of that seemed to

make a difference. I also experimented with different sight holds. The sight

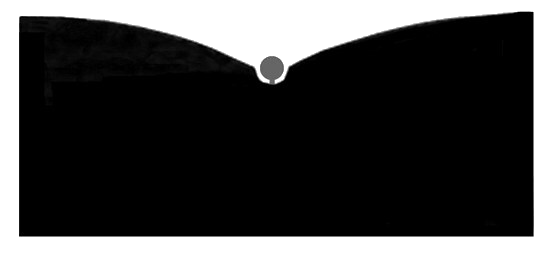

picture looks like this:

The rear sight appears as a shallow valley, with the front sight appearing as a ball

on a stick. It seems that centering the ball in the valley left-right, should give

you a fairly consistent windage hold, yet I was getting a lot of off-to-the-side

flyers.

My first inclination was to bury the ball into the valley so that no stick is visible,

however I later decided that some stick showing was better because you can then more

precisely see that the front sight is centered in the valley for windage. But then

that means that you don’t have a real positive reference for how high the ball should

float above the valley for elevation hold.

Then I played around with the front sight ball covering the target bull, or should it

form a figure-8 with the target bull? Halfway covering the target bull? If I could

keep them all in the black, at least at 50 yards, that would mean that I could give

javelina hunting with a muzzleloader another try, but so far, no luck with that.

I finished the day shooting 10 of the Hornady Great Plains conical bullets. I did

seem to achieve greater consistency with these bullets than with PRB. These shoot a

lot slower than the PRB because they are twice as heavy. I had to bring the rear sight

up many clicks to get the holes into the black:

I wish I could tell you that those were two 3-shot groups with a sight adjustment

in-between, but it wouldn’t be true. At least the windage showed good consistency

among my final six shots of the day.

I had taken about 50 shots over the course of the day, and though I had been swabbing

the bore between shots, the crud was really starting to build up around the nipple and

the back of the barrel (see lock area smoke in the

first photo). I decided that it was time to quit and give the gun a good cleaning.

The time tested technique for cleaning a traditional muzzleloader is to remove the barrel

from the stock and soak the breech in a bucket of hot water, maybe with a little soap,

and to pump the hot water up and down the barrel, through the nipple and/or nipple hole

at the back of the barrel, using you ram rod, jag, and patches.

I like to loosen the nipple at first to pump the water through the nipple, and so that

some water leaks past the nipple threads to clean them. Then I remove the nipple so

that the water pumps through the barrel and breech with higher volume and velocity.

I found that a clean, unused, 1-gallon paint can from the hardware store is just about

ideal for this task, as it can be heated on a stove burner. The hot water does a good

job of heating the barrel, so that once you remove the barrel from the bucket, the water

evaporates quickly. But most importantly, the hot water dissolves the corrosive salts

deposited by burning black powder (or BP substitutes). After the barrel dries, you then

dress the bore and the outside of the barrel with moose milk, bore butter, Ballistol,

or other natural gun lube to leave a thin layer for rust prevention.

I’ll be the first to admit that I am a rank amateur at this muzzleloading stuff. I know

just enough to be able to make it go BOOM, most of the time. There are nuances and

subtleties involved in loading a traditional muzzleloader to achieve best accuracy.

There is much to learn.

For example, after getting home from my disappointing range session shooting PRB, I read

that round ball inaccuracy could be due to not centering the ball perfectly on a pre-cut

patch when loading. A cure? Start the ball in a pre-lubed strip of patch material

(“pillow ticking”) and cut off the excess with a knife flush at the muzzle before

seating the ball fully down the barrel. That way, the patch wraps symmetrically around

the ball every time.

Another thing I want to try is saboted .44 caliber pistol bullets. Saboted bullets are

something that I never tried back in my Grey Hawk days.

Inspired by a TV show, I got the rifle mainly as a fun and cool range toy. If I can

figure out how to get it to shoot accurately enough to hunt, well that would just be

gravy.

![]()