| Articles | Documents | Equipment | Events | Links | Membership | Miscellaneous | Scrapbook | Targets | What's New |

| My Own C.S.S. Merrimack | September 1997 | |||

| Dan Martinez | ||||

My 6 year old son, Bennet and I awoke around 4 A.M. We were headed to Horseshoe

Lake to make the annual attempt to down a Christmas goose.

On one other waterfowling adventure to Horseshoe two years prior, I actually

had geese fly close enough for a shot. Unfortunately, the only 12 gauge I owned

wore a scope and a .223 rifle barrel, so my 20

gauge O/U was pressed into service as a waterfowl gun. Loaded with #2 steel shot,

the heaviest load you can find in 20 gauge, it was no match for the big Canadians.

I fired two shots in their direction, but they never missed a beat.

I was ready the next season, having picked up a synthetic-stocked Remington 870

Express in 12 gauge. Despite a memorable trip to Mormon

Lake where it performed yeoman's service by knocking down a number of ducks, I

never did get a chance to test it on the big honkers that season.

Which brings me back to December 1996. Ben and I pushed off from the boat ramp in

the pre-dawn darkness. The electric motor purred quietly as we took off across the

lake toward the Verde River end. We found ourselves in a marshy area looking

eastward with a tall screen of vegetation behind us, separating us from the main

river channel.

As the sky lightened we saw a few flocks of ducks flying around, but none came in

range. Then I heard it: the unmistakable sound of Canadian honkers. At that point,

I had no idea of where they were, but I fished around in my vest for my goose call

anyway. I really didn't expect to be able to call them in - I only wanted a chance

to talk to them. But after about two honks from my horn, they came into view!

There were five of them, forming a mini-V, about 500 yards out - and they were

headed right toward us! I frantically worked the pump, jacking out the #3 duck

loads, and jacking in the 3" magnum load of steel BBs. I even managed one or two

more honks during this time, to keep 'em coming.

As I finished getting the third round into the gun (two in the mag and one in the

chamber), I pointed the 28" barrel at the V. They were definitely flying low

enough for a sporting chance, they just needed to get a little closer . . . Come

on, come on . . . but at about the 70 yard point, they must have sensed that

something wasn't kosher. They suddenly veered and flew off up river! Damn!

This is one of those scenes that's gets played over and over in your mind. That

night while lying in bed around midnight, the tape of the encounter was playing in

my head. What had gone wrong? Obviously we were just too visible. We were

sitting in the canoe facing east, into the sun. The birds were flying westward,

toward us, and the brightening eastern sky must of had us well illuminated, even

though the screen of vegetation behind us would have helped to break up our

silhouettes. But obviously that wasn't enough.

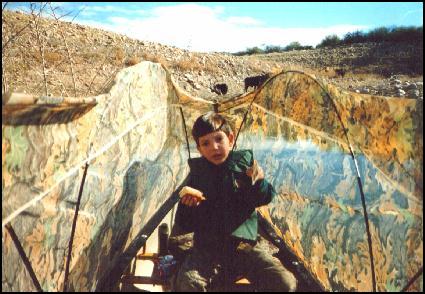

That's when it hit me; the idea that culminated in the image you see on this page;

the idea to blind my canoe. Yes, I actually got up out of bed, grabbed some spare

tent poles I had laying around, and mocked them up on the canoe on the backyard

lawn in the middle of the night.

I call the finished product my own Merrimack, because to me, in profile, it

resembles the famous

Confederate ironclad battleship that fought the Union's Monitor to a draw. (If

I would have called it the C.S.S Virginia, most people would have no idea of what I

was talking about.)

Building the Blind

The first thing I did was head to Popular sporting goods to check out what kind

of replacement tent pole kits they had. It turns out that they had two sizes:

7mm and 9mm. Each kit contains 4 poles, shock cord, and an assortment of

ferrules. I opted for 4 of the 7mm kits at $7.99 each.

I assembled one of the kits into a 4 pole loop and held it in place on the

gunwales of the canoe. It looked to be the perfect height. I wanted the tops

of the loops to be about at eye-level. That way, only the top of the head is

normally exposed, and if more concealment is needed, all you've got to do is

hunch down a little. And at that height, it's still easy to peek over the top

for a clear view.

The next problem to solve was how to attach the poles to the canoe. The method

had to be easy to put up and take down, since I cartop my canoe. Checking out

the ferrules supplied in the tent pole kit, I found one that slips onto the end

of the pole and ends in a reduced diameter peg.

First I drilled a hole slightly larger in diameter than the peg, but smaller than

the main body of the ferrule, all the way through both sides of the hollow vinyl

gunwale. I drilled the hole through at an angle instead of straight down to

lessen the bending stress that would be applied to the poles. Next, I opened up

the top hole only, large enough to accept the main body of the ferrule.

With seven more such holes drilled, the poles were assembled and placed into their holes. Now, the hoops on each side of the canoe look something like this:

Next problem: How to get the camouflage netting onto this framework. I had some netting already, but not enough for this project. I'm using plastic netting (polypropylene?), not burlap, because it dries fast and does not rot. I needed enough to go around the entire perimeter of the canoe. My canoe is 14½' long, so I needed about 10 yards total. Close to my home, Phoenix Sports (now JumboSports) sells this netting off of big rolls about 4½ feet tall for $3.99 a yard. I already had about 4 yards, so I went to the store with the intent to buy 6 more. But when I saw that the guy was measuring yards by spreading his arms wide and saying, "One yard . . . ", I decided that maybe I didn't need another 6 yards after all. (People have an armspan very close to their height, so a six footer would actually be measuring two yards each time.) When I got home, to help me think about how I was going to get the netting onto the frame, I temporarily attached it to the hoops with clothespins. The canoe was sitting on my backyard lawn, with the bottom of the netting just brushing the grass. This way, the entire hull is covered by the netting to the waterline. Set up this way, the netting comes about 12" over the top of the hoops. This extra material was simply folded over the top of the hoops and clothespinned in place. The blind was taking shape, but at that point, it was looking like I would need those clothespins to hold the blind in place out on the water. Well, the very next thing that needed to be done, was to attach my four yard piece of netting to the new netting I had just purchased. So I dug out my wife's sewing machine and reacquainted myself with its operation. After zigzagging the two pieces together, I now had one large piece of netting that would go all the way around, plus. It was actually about four feet too long. When it came time to sew the netting together into one large loop, instead of cutting off the excess length, I left it, which gave me about a four foot long area where the netting is doubled.

So now I have a continuous loop of netting mocked up all the way around the canoe, and it's starting to become clear what I need to do. In the napkin sketch above, the dotted lines represent where I ended up zigzagging with the sewing machine. Out in the backyard, a technique I found very helpful in fitting the netting to the boat is basting. No, not the kind where you squeeze juice over a turkey to keep it moist. Rather, basting is temporary hand-sewing, using very large stitches, to hold the article together until you can do it over again with the sewing machine. Believe it or not, this is something I learned from my great-grandmother back when I was but a wee slip of a lad.

Sewing the folded-over top of the netting around the tops of the loops created four little "pockets" which serve well to hold the netting onto the loops. Clothespins are no longer necessary. From the top of the hoops to the bow and stern points of the canoe, the netting also gets sewn together. This leaves a couple of useless triangular patches of material which were simply snipped off. I only got one chance to field test the Merrimack before the end of the season last year. The weather was warm and clear, in other words, not very ducky. I did get off one good shot as I jumped a quacker while drifting into a small water pocket. My shot was behind him, but I did manage to singe some tail feathers. After he flew past, feathers settled into the water for the next minute or so. I am able to report, however, on the rig's handling with the blind in place. The blind was erected at the boat ramp before getting underway. The sticks go up fast, and actually, I was rather surprised at how easy it was to unfold the netting and get it hung on the loops. There is a cutout for the electric motor, and this serves as an effective index mark for orienting the netting on the boat. Once underway, There were no issues with steerability, or with the netting getting hung up on floating debris. To get into or out of the boat, you simply lift up the material and go through one of the hoops. Visibility for the rear-seated captain is somewhat of an issue, but not a major problem. If needed, I foresee no major problems with leaving it undeployed until anchored at a likely spot, and then deploying the blind from within the boat.

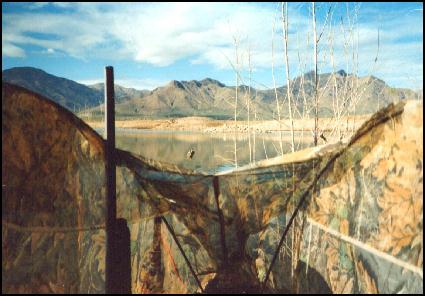

Compared to the open boat, you do get this sort of warm and fuzzy cocoon kind of feeling inside the Merrimack. I'm sure that it helps to deflect some wind, even though the netting is a fairly open weave. Blinding of the occupants is much better in the section where the netting is doubled up. I think you can see that in the first photo in this article. Near the back half, by the motor, is where the material is doubled. Up front is only a single layer of the material, and rocks behind the boat can clearly be made out. I may yet sew another layer of material to the front section of the blind. I lost one ferrule off of one of the pole ends after this first field trial. I found that a sawed-off .223 shell is an effective substitute. I'm looking forward with great anticipation to the upcoming waterfowl season. If I can get out on the water at Mormon Lake, I expect I'll be a real duck slayer. And if I'm really lucky, maybe this will finally be the year for that Christmas goose. © Honeywell Sportsman Club. All rights reserved. | ||||

The Honeywell Sportsman Club is a small group of shooting and outdoor enthusiasts in the

Phoenix, Arizona area. Our website is ad-free and completely free to use for everyone.

But we do have expenses that we need to cover, such as the web hosting fee and our liability

insurance. If you enjoyed visiting our website, found it useful in some way, or if you enjoyed

reading this story, please consider tipping us through our PayPal donation jar below. Thanks for visiting, and come back soon.

![]()

Articles

Docs

Eqpt

Events

Join

Links

Misc

New

Pix

Targets