When I was growing up, my Dad owned a certain deer

rifle that was somewhat of an instrument of awe among us young'uns:

a "Springfield thirty-aught-six". He also had a Remington Wingmaster

in 16 gauge that I wrote about a short time ago, and a Red Wing

recurve bow.

In time, after Dad left this world, possession of the Remington and

the Red Wing passed to me, but not the Springfield. Family history

is a little murky about whatever happened to the aught-six, but it is

my belief that he sold it off sometime while I was in my teens.

Dad was always more of an avid High Sierra trout fisherman than he was

a hunter. He went on his few hunting trips more to be with the boys,

my uncles, than because he liked to hunt. After a while, he just hunted

less and less, so I can see why he might have gotten rid of the rifle,

maybe to be able to afford Christmas presents one year - I don't really

know.

These days, I am much more of an avid rifleman, than I am a fisherman, a

pistolero, a bowhunter, or even a shotgunner. So not having possession

now of Dad's old Springfield has been a great disappointment.

I can remember hefting the rifle under Dad's watchful eye when I was small.

It felt solid and heavy. The rifle was different than most other deer

rifles I had seen because it had a "blonde" stock, not a brown one. When

I lifted it up to my shoulder, I remember how the stock's cheekpiece felt

against my cheek, and how it aligned my eye perfectly behind the scope.

And oh! That man-sized thirty-aught-six cartridge! Wow! Tales of the

heavy kick when the gun was fired only added to the awe and wonder

surrounding the rifle. ("What does

'aught'

mean, Dad?") I remember Dad showing me the bruise marks left on his shoulder

after a day at the range.

These memories colored the choice of MY first bolt action deer rifle.

I wasn't necessarily looking for a .30-06, but since that was Dad's caliber…

But I sure didn't want those bruises! Even though I was 36 years old at the

time, and a fairly big guy, I was still worried enough about kick that the

.30-06 rifle I picked was equipped with a muzzle brake, a Browning with BOSS.

At the time, and for many years thereafter until I became a real gun nut, I

didn't realize that Springfield was not just another firearms company like

Remington or Winchester. I thought that Dad simply went down to the gun

store and bought himself a new Springfield off the rack. I didn't realize

or understand that his rifle was a custom sporter built from an old military

rifle. Which brings me to a couple more unknowns concerning the origin of

his rifle: Where did he get it? What's the story behind its custom

sporterization?

With my recent interest in bolt action military rifles, about a year ago, I

picked up my first, very own Springfield. It's a World War II vintage

Smith-Corona '03A3 in all-original dress. The stock is nicely distressed,

like it's seen some serious use, but the metal is in generally excellent

condition. I think it's extremely cool that it's a war-time rifle

manufactured by a typewriter company!

The rifle is not some target-shooter's range queen. It fits in well with

the rest of my collection of battlefield leftovers. This rifle was my first

opportunity for up close and personal familiarization with a Springfield rifle.

"Dad's Springfield" custom sporter (top), original Smith-Corona '03A3 (below)

Five months later, I was back at the gun show yet again, browsing up and down

the aisles of tables with my younger son, Sam. I was stopped dead in my tracks

when I spied, on a table full of rifles, Dad's old Springfield! Now bear in mind

that its been about 35 years since I had last seen Dad's Springfield. In fact,

I was probably pretty close to Sam's age. But from muzzle to ventilated

buttpad, the rifle now before me was exactly what I remembered Dad's was like!

"Whoa, Sam. That rifle looks just like my Dad's!"

"That sure is a nice looking rifle, Dad," Sam replied. After a thorough

lookover, I put the rifle back down on the table and started to walk away. As

usual, I didn't have much dough in my pockets. Certainly nowhere near enough

to meet the seller's asking price. I got about two tables away, stopped, turned

around and looked back in the direction of the rifle. I don't know what it is

about Sam, but he has this uncanny ability to read my mind. Like the little

devil that rides along on your shoulder, he says again, "That really is

a nice rifle, Dad."

"It sure is, Sam. And I'll probably never see another like it." Of course I

didn't really think that it was Dad's rifle, just the closest thing to

Dad's old Springfield that I had ever seen.

Fate was sealed. It had to go home with me. We made a beeline for the

exit and got our hands stamped so that we could return. I headed straight to

my bank's ATM and withdrew adequate funds to make the buy. After a quick lunch

stop, it was back to the show.

I was able to negotiate a few bucks off the asking price, but it wouldn't have

mattered if the seller had raised his price; Dad's Springfield was coming home

with me.

Some details: A serial number lookup reveals that this rifle started life in 1918

at the U.S. Springfield Armory as a U.S. Rifle, Cal. .30, M1903. At first, I

thought that the rifle had been commercially rebarreled, but a close look near the

muzzle shows the remnants of a military date stamp that has been all but polished

out. The entire barreled action has been highly polished and deeply reblued.

The bolt or maybe just the handle, has been replaced with a dished, scope

compatible sporter version. The original military safety lever has been

similarly replaced with a low-swing version.

The original two-stage military trigger system has been replaced with a Timney

unit. The action has been drilled and tapped to accept a one-piece Buehler scope

mount and Buehler rings. Riding in the rings is a 50's to 60's vintage Lyman

All-American 6x Perma-Center scope. Optically, this scope is still very clear and

bright.

Perhaps the rifle's most striking feature, is the tiger-striped maple stock.

Featuring a teak grip cap and forend tip, the stock is a stellar example of what

has come to be known as a "California style" stock.

The "California Sporter" is a stock design developed by Roy Weatherby beginning

in the late 40's. The design probably reached the zenith of its popularity in

the mid-60's. The design came to be identified with California because Roy

Weatherby was based near Los Angeles.

The features which set a California Sporter stock apart are a pronounced Monte

Carlo cheekpiece, sometimes exaggerated to the point of a rollover cheekpiece.

The comb of the stock will slant downward toward the rifle action. A tapering

flat-bottomed forend profile which terminates in a reverse slant at the front

where the forend meets the barrel is a signature design feature. Normally,

there's a contrasting forend tip and grip cap, set off by light colored wood

spacers. The grip curve is tight, the grip itself extended, with a noticeable

flare. There are usually diamond inlays in the stock, at least on the grip cap.

The stock would often be finished with a high gloss polyurethane.

This stock design was sometimes taken to grotesque extremes in its heyday.

Thankfully, "Dad's Springfield" (the quotes here signifying the rifle I now own

that looks like my Dad's old Springfield), avoids the excesses of the design.

The cheekpiece does not rollover, there's only one diamond inlay in the face of

the grip cap, and the finish is satin, not high-gloss polyurethane. It's enough

"California" to serve as a fine example of a design now beginning to get old

enough to qualify as classic, while not totally offending the modern "less is

more" preference in stock design.

And how about those tiger stripes! Wood grain with vertical, grain-crossing

stripes such as these is also called curly, or fiddleback. It's fascinating to

observe the stripes under a good light - as you change the angle of the rifle to

your eye, the stripes will "move". What was a dark stripe smoothly changes to a

light stripe and vice versa. As a matter of fact, the vertical stripes on this

light colored stock make for a rather effective camoflage pattern wherever you

may find yourself in a dead grass habitat.

As fate would have it, my Mom was visiting that weekend. When Sam and I got

home, I was greeted with, "Alright Daniel, what did you buy?"

My reply was simple. "Dad's rifle."

A puzzled look crossed her face. "What? What do you mean?"

"I found Dad's rifle at the gun show." I briefly left her as I went to

retrieve the rifle. I walked up to her and placed it into her hands. A

strange kind of misty smile came across her face.

"Oh my God. Is it … really Dad's rifle?"

Now that I got it home, I had a chance to fully check out the rifle. I found

out that mechanically, not all was milk and honey. The trigger pull was very

inconsistent, and striker travel seemed rather weak. Furthermore, the safety,

while operable, just kind of flopped around. The original military magazine

follower was designed to not allow the bolt to be moved forward when the

magazine was empty. Though the follower had been ramped, to allow the bolt to

override and push down the empty follower, it was still a little balky.

Sometimes, when the bolt was operated vigorously, the bolt would go forward,

turn down, but then something would lock up so that you couldn't lift the

handle again, except by really horsing it.

So that's why he was getting rid of it, huh? Such are the risks of buying a

used rifle. On the other hand, I've had very good luck at remedying the little

problems of neglect frequently found in used rifles that no one has spent recent

loving attention on. Often, all an old rifle needs to be happy, is a new and

attentive owner.

So it was with this rifle. I took it apart to investigate the mechanical

anomalies. The first thing that I found was that the Timney trigger unit was

simply not installed correctly. This was my first experience with a Timney, but

it didn't take me long to realize that the trigger unit was just dropped in

without being tightened down. Then some experimentation with the pull weight

and overtravel adjustments resulted in a very sweet, yet reliable trigger.

I broke out the Dremel and set to work on the magazine follower. I increased the

ramp cut a little more and polished the edges of the cut. This resulted in a real

improvement in bolt closure on an empty magazine.

I started a search for a new safety lever that wouldn't flop around. What I found

was a complete new bolt assembly with a low-swing safety. My plan was to use the

new safety on my old bolt, so that I wouldn't be potentially messing up the

headspace. Then I was going to use the fresh striker spring to speed up striker

release. I made the spring swap, then started trying to figure out how to remove

the safety lever. Instead, I discovered that all it took to remove the slop from

my original safety was to make a very slight bend in a tensioning ear on the safety

lever and it was good!

And it turned out that my problem with bolt lockup with vigorous operation was

merely a side-effect of the floppy safety. The safety would occasionally flip up

unnoticed into a sort of half-safe position which had the effect of locking up the

bolt. So with the safety fixed, the bolt lockup problem disappeared.

I didn't draw an Arizona deer tag this year, but I did get my very first

out-of-state deer tag. I was heading to Montana to hunt with fellow club member

and good buddy Dale Saverud. With all the initial mechanical problems I had with

this rifle, I never figured that Dad's Springfield would be hunting this season.

But when the last problem was finally solved, this rifle suddenly became the top

pick.

There was one more thing I had to do to the rifle before I could take it hunting --

add sling swivels. This is how I know for sure that it's not really Dad's rifle.

I remember that Dad's rifle definitely had a sling on it. When I brought this rifle

home, it had no facility for mounting a sling.

I started load testing with my favorite .30-06 load that I use in the Browning.

This loads throws the 165 grain Nosler Ballistic tip at 2800 fps. Hey! I don't

remember this load kicking so hard! And it doesn't, not in the muzzle-braked

Browning. But in the Springfield, you definitely get the full effect! On top of

that, the Springfield wouldn't group this load worth a damn.

Time for a new plan. This is an old military rifle, right? So why not go with a load

more like the rifle was used to? I decided to aim for a load which threw a 150 grain

missile at 2700 fps. These are the specs for the old M2 Ball military load. The

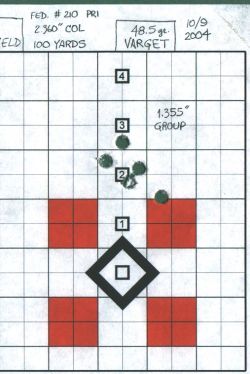

recipe I ended up with was the 150 grain Hornady SST over 48.5 grains of Varget lit

by a Federal #210 large rifle primer.

Grouping was not benchrest quality, yet highly satisfactory for an 86 year-old battle

rifle turned into a civilian meat-getter. I sighted the rifle in to hit two inches

high at 100 yards, where it was printing groups in the 1.3 to 1.5 inch range.

I was really hoping that I could have punctuated this story with a photo of me, the

old Springfield, and an old big-horned Montana buck, but alas, it was not to be. Dale and

I hunted hard for a full week, and though we saw plenty of deer, we never chanced upon

one with horns. So it goes.

So no, it's not really Dad's rifle. But every time I pick it up, it reminds me of him.

Isn't that what really counts?

![]()