| Articles | Documents | Equipment | Events | Links | Membership | Miscellaneous | Scrapbook | Targets | What's New |

|

Gun Report: .444 Marlin The Forgotten Big Bore | July 1998 | ||||||||

| Dan Martinez | |||||||||

In recent years, the round known as the .444 Marlin has been greatly overshadowed

by its older, bigger brother, the .45-70 Government. Both are long, straight-wall,

big bore rifle cartridges. There are plenty of good reasons that the .45-70 gets

all the press. Not the least of which is a long history with a rich heritage.

New developments in the firearms industry, though, are making it worthwhile to give

the forgotten .444 a second look.

The .444 Marlin was designed by Remington at Marlin's request in 1964. To digest

the new round, Marlin beefed-up their venerable model 336 .30-30 lever action and

dubbed the result the Model 444. The .444 Marlin cartridge is little more than a

.44 Magnum with an extra inch of cartridge capacity. It's a little demeaning to

say that it's "nothing more" than a lengthened .44 mag, because that extra inch

of powder buys you at least 600 fps more velocity in a comparable length barrel.

That's nothing to sneeze at. In terms of muzzle energy, that extra inch causes

.44 caliber projectiles to be pumped out at .30-06 power levels.

The .444 Marlin does use .429" pistol bullets. And therein lies the root of this

cartidge's second place status to the .45-70. Because bullets of .429 inch diameter

are designed for such rounds as the .44 Special, .44-40, and the .44 Magnum, they

are in general, too lightly constructed to be thrown around at velocities exceeding

2000 fps. The average bullet used in the .45-70 is better matched to the grand old

cartridge's velocity capabilities.

But the .45-70 also has its own old baggage to haul around. That old baggage takes

the form of the 1873 Trapdoor Springfield rifle, and other original and replica arms

of the late 19th century. Because there are plenty of these weak action firearms

around, and no fewer unknowledgeable shooters, the major ammunition manufacturers

load the .45-70 only to the 28,000 C.U.P. pressure level. On the other hand, since

the .444 Marlin was originally chambered in a modern rifle, the pressure standard for

the modern cartridge was set at 44,000 C.U.P.

Marlin introduced a .45-70 lever gun based on this very same rifle in 1972. This rifle

was given the name of their original .45-70 lever gun which was discontinued in 1915,

the Model 1895. Now we have a .45-70 rifle capable of handling the .444's pressures,

and knowledgeable reloaders took advantage of that. Still, since the .45-70 uses

bullets that start at 300 grains weight, and the lone factory .444 load uses a 240

grain bullet, velocity and trajectory still favor the .444.

So here's a quick summary of .45-70/.444 Marlin pros and cons: Favoring the .45-70:

Stoutly constructed real rifle bullets available in weights up to 500 grains give

excellent penetration. Favoring the .444: Shoots lighter pistol construction bullets

faster for a straighter trajectory and devastating expansion. Factory loads for the

.444 develop significantly more power. If you happen to get into the position of

deciding between these two Marlin rifles, the rule of thumb is to get the .45-70 if

you're a handloader, get the .444 if you're not.

Though I am a handloader today, when I bought my Marlin 444SS, I wasn't. Even if I

were making the choice today, I would probably still opt for the .444. Why? Well take

that name, the Marlin Model 444SS. Let me throw some other numeric model numbers at you:

454SS, 429CJ, 455HO. For those of you who don't recognize these numbers, they are the

engine designations of the most powerful Detroit factory hot rods ever built, the Chevy

454 Super Sport, the Ford 429 Cobra Jet, and the Pontiac 455 High Output. For me, Marlin

hit the marketing nail square on the head when they chose their cartridge designation.

Their number makes such an easy association to big power.

So what are those S's on the Marlin's name? The rifle was introduced as simply the Model

444 with a 24" barrel and a straight grip. Later the grip shape was changed to the

current curved pistol grip shape, and the barrel was shortened to 22". They called this

the "Sporter" configuration, and the first S was added. Still later, the cross-bolt

hammer-blocking safety was added, and the rifle's model designation grew its second S.

So for many years, there was only one gun and one factory load designated .444 Marlin.

And yes, today there is still only one factory loading of the .444. A 240 grain flat

nosed softpoint loaded by Remington to an advertised velocity of 2,350 fps. But I don't

expect this to remain the lone factory load much longer. Why?

In the last couple years, the Marlin 444SS has been joined on the firearms market by no

less than 6 new guns chambered for the .444 Marlin cartridge! The Magnum Research Lone

Eagle cannon-breech single-shot handgun in .444 has been on the market for several years.

In 1997, Beretta announced the Silver Sable double rifle, and Thompson/Center announced

their Encore single shot handgun in .444.

And this year the momentum continued with the reintroduction of the Remington Rolling

Block single shot rifle in .444. For 1998, USRAC threw in the towel and chambered their

Model 94 Big Bore lever rifle in .444 Marlin. Rounding out 1998's .444 announcements is

the mid-year introduction of the BFR by Magnum Research. The BFR (Biggest Finest Revolver)

is a single-action 5-shooter available with a loooong cylinder capable of chambering not

only .444 Marlin, but also .45-70 and .410 shotshells.

That makes three handguns chambered in .444 Marlin. These must be for men manlier than I

am. Before I put a Pachmayr Decelerator buttpad on my rifle, I could stand to shoot no

more than about a dozen rounds off the bench. This cartridge is a kicker! The

Decelerator goes a long way towards making the gun more pleasant to shoot. As issued,

the Marlin comes with a hard, thin rubber butt plate that really has no usefulness

whatsoever for recoil absorption.

The new guns are one big factor in the revival of interest in the .444 Marlin. The

other factor is the recent introduction of premium handgun hunting bullets in .429

inch diameter. These new bullets have the potential to transform the hunting

performance of the .444 Marlin cartridge. Three examples are the Nosler Partition HG,

the Swift A-Frame, and the Barnes X solid copper pistol bullet. I was able to get my

hands on a box of the Partitions for some recent testing.

But, the Nosler Partition HG is not ideal for the Marlin, either. It is designed with

a large hollowpoint for rapid expansion at pistol velocities. The portion of the bullet

ahead of the partition is rather shallow, with most of the bullet's weight behind the

partition.

For best performance in the 444SS, it's imperative to use jacketed bullets, not lead.

The 444SS uses Marlin's Micro-Groove rifling in a 1 turn in 38 inch twist. Lead bullets

tend to "skid" in the shallow rifling and give less than satisfactory accuracy. The

other problem is caused by the slow twist rate. My experience has been that 300 grain

bullets are not stabilized in the Marlin's barrel. Out of 30 shots on paper at 100

yards, 5 hit the target sideways, keyholing.

(Reader Jorn from Norway offers the following tip: "I have had several Marlin rifles,

both in .44 Magnum and in .444 Marlin. And I have gotten great results from both of

them shooting cast bullets, BUT the bullets must be sized to .432 dia. Most cast

bullets are .430 and that is too little for the Marlin grooves. By slugging the barrel

you will see most of them indicate a diameter of .430, so shooting cast bullets in .430

is too little.")

My primary purpose for owning the Marlin is for cow elk hunting. The .444 is at its

best under 150 yards, which is plenty for hunting cow elk. If I ever get lucky enough

to draw a bull tag, I would instead opt for my .30-06 using one of the Federal High

Energy loads. Unfortunately, since I've owned the Marlin, I've only had a chance to

chase elk with it for two days, without seeing any.

Elk are big animals, and the Marlin is a moderate range rifle. Accuracy is not an

issue for my purposes. At 100 yards, I'm getting just over 2" groups, with my best

loads. When I run into elk out in the woods (typically when I'm hunting turkeys), they

are very often within 100 yards. Accuracy is not the challenge, penetration is.

For hunting any elk, penetration is the primary attribute you want in your rifle and

load combination. I finally got around to performing some penetration testing with

the Marlin that I've been wanting to do for a long time. It was finding the Noslers

that gave me the final push I needed.

I had never done any penetration testing before, so this was a heck of a lot of fun.

For several weeks, every time I walked out the door at work, I stopped by the bin where

people had been throwing last year's phone books for recycling, and tucked a pair under

my arm. I wanted to test at least 5 different bullets, and I figured a maximum

penetration of 24", so I didn't stop until I had 10 feet of old phone books stacked up

in my garage!

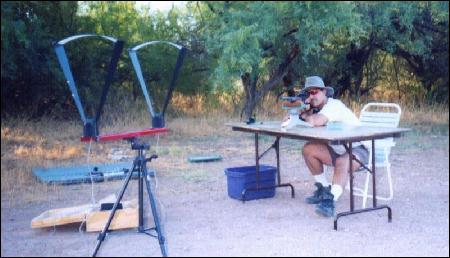

Then I built myself a caddy, a crate kind-of-a-thing in which to stack the wet phone

books. To have better information about the loads I was shooting, I borrowed the

club's chronograph. This was also the first time I had ever played with a chronograph

in any of my rifle testing. I've got it now, just try to get it back from me! (Just

kidding.)

I have a large Rubbermaid tub that I put in the back of my truck and loaded with phone

books. Then, I three-quarter filled the tub with water and put the lid on. The tub

will only submerge enough books for 2 or three shots, so the testing actually took me

three trips out to the desert. I performed my testing in the open area behind the tank

at our Desert Shotgun range. I fired into the wet phone books at a range of 75 yards,

figuring that would be a realistic range for shots at cow elk.

For each bullet tested, I first took a couple of sighting-in shots at a paper target

parked next to the penetration test crate. I needed the confidence that I would center

the phone books when I took the shot that counts.

Most elk are shot with bolt action rifles nowadays, and the ol' .30-06 is considered by

most to be the standard against which to compare all others. The traditional elk

hunting bullet weight in the .30-06 is the 180. So I shot some .30-06 loads into the

same test media for comparisons.

As you can see in the preceding chart, I shot four different .444 Marlin loads, and three different .30-06 loads. I didn't make any special effort to get the finest elk bullets available for the .30-06, I just shot what I had on hand. For the .444, I started with the Remington factory load. Though factory spec'ed at 2350 fps, the particular bullet that found its way into the wet phone books clocked only 2234. The sighter I shot first, did clock over 2300 fps, but unfortunately, I did not record that reading.

The first handload I shot threw the 265 grain Hornady softpoint at close to 2200 fps. Hornady says that they created this bullet specifically for the .444, building it with a heavier jacket than their normal pistol bullets. It turns out that in terms of terminal effect, the Remington 240 and the Hornady 265 are near ballistic clones. Both expanded greatly and symmetrically to about ¾", into a nearly flat button. Both penetrated to exactly the same depth, 13-3/8". Both retained very close to 100% of their weight, neither showing any tendency for the lead and jacket to separate. The next bullet to go sledding through the wet paper was the Nosler Partition. This bullet demonstrated dramatically different performance. As I suspected would happen, on impact, the front partition of the Nosler exploded with violent expansion and was simply blown away. The Nosler's nose jacket is pre-cut in six places, so what little jacket was left from the front section, formed a hexagonal shaped front to the 203 gr. full wadcutter which remained. This .510"x.565" hexagonal wadcutter penetrated the deepest of the seven bullets fired - almost 21 inches!

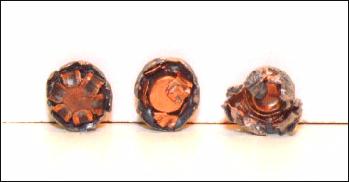

The final bullet tested in the 444SS was the 300 grain Speer Uni-Cor flatpoint. This bullet was not really a contender for the hunting bullet of choice in my Marlin because of the aforementioned stability problems. I just wanted to see what the Marlin was capable of with 300 grains of lead. And I wasn't disappointed. The Speer is made with a somewhat thin jacket which is plated onto the lead. Enough copper is deposited to form a true jacket, unlike some of the cheapy cast lead bullets which only get sort of a copper-wash plating. Anyway, this bullet exhibited the most dramatic entrance "wound" of all the rounds fired. The effect of the explosive expansion of a full 300 grains of lead is truly a sight to behold. See the first photo in this article. The slug practically turned itself inside-out. And yet, the bullet did hold together in one piece. Even with such extreme expansion, the Speer came to rest only after having travelled 13½". And when it did stop, it still held 92% of its original mass. But the asymmetric form of its expansion hints at that stability problem with 300 grain projectiles. The lead was definitely flowing from one side toward the other during the process of expansion. See the photo below which shows the backs of the three flatnose softpoints to compare their expansion characteristics.

I have considered rebarreling my gun with an octogonal barrel in a 1 in 24 twist so that it could handle 300 grain bullets. But such a job would double the original cost of the gun, and there are lots of higher priority projects to which that money could be applied. How does the 13½" penetration stack up compared with the "standard" elk load of a 180 grain projectile fired out of a .30-06? That was the first bullet fired for comparison testing. I don't know who the manufacturer of this particular bullet is. It's just a conventional construction 180 grain softpoint hunting bullet I had laying around my reloading bench. It penetrated about ½" less than the "standard" .444 Marlin loads, suffered significant weight loss, and the core squeezed out of the jacket during expansion much like toothpaste squeezes out of its tube. The flat button of core lead was recovered just in front of the jacket, but they had definitely come apart during the expansion process. It was evident that as the lead fed forward out of the jacket, the leading front of the lead was being ablated away. Though the jacket was recovered in one piece, with no obvious parts missing, the total recovered weight of the two pieces together was only 118 grains. The bullet had suffered a 44% loss in weight. The obvious conclusion is that at 75 yards anyway, the plain old factory Marlin load is greatly superior to the standard .30-06 180 grain load. However, at ranges longer than 175 yards, this conventional construction .30-06 would probably outperform the Marlin load because of better long range energy retention. The next bullet tested is my standard mule deer bullet, the Hornady 165 gr Boat-Tail Soft Point. This bullet is one step ahead of conventional construction, but it is not one of the highly-touted "super-premium" bullets. It is made with Hornady's "Interlock" construction. With this bullet design, there is a ring of jacket material which projects inward, into the lead core, from the jacket. This ring is placed at the point on the shank of the bullet where the bullet designer wants expansion to stop. This bullet appears to have performed exactly as designed. Boat-tail bullets have a reputation for allowing their cores to slip out of their jackets. The Hornady #3045 showed no evidence of this whatsoever. Admittedly, this load was a little short of powder. I just switched from IMR4350 to H4350, and have been doing the good reloader bit, by starting mild. This pill was launched over 200 fps short of full speed. Regardless, it still came in as the third best penetrator of the seven bullets tested, beating all the Marlin loads except the Partition. Weight retention was 70% The final load is one of those highly touted super premiums - the Speer Grand Slam. This bullet features a dual-composition lead core, soft up front, hard, high-antimony at the rear. Both cores are poured into the jacket hot, and "solder" themselves to the inside of the jacket. In addition, at the interface of the two lead alloys, the Grand Slam incorporates an inward-projecting ring similar to the Hornady Interlock's. This is a rather pricey bullet. And it did outperform the less expensive Hornady. This bullet was fired at 99% full speed, yet it retained 79% of it's initial mass and penetrated second best at 17-1/8". So what are my conclusions after all this testing? An interesting observation is made when you pick up one of the recovered .30-06 bullets, put it down, then pick up one of the expanded .44's: Like when Lloyd Bentsen told Dan Quayle, "you're no Jack Kennedy," an expanded .30 caliber bullet is no expanded .44. The best .30-06 in my test weighed 130 grains after doing its work. The lightest recovered .44 is 203 grains, and it traveled almost 21 inches. Is the Nosler Partition the new super bullet which will at last bring the .444 Marlin the awe and respect it so richly deserves (says the .444 fan)? The jury is still out. The way the Nosler loses its nose on impact, continuing as a basically unexpanded solid, leaves me rather cold. What would happen if we filled the nose cavity with molten lead, though? An interesting question. It would have been nice to get a hold of the new Swift and Barnes bullets to play with. Maybe somewhere down the road. Another interesting observation I made comparing the impact of the .444 loads to the .30-06 loads, is that when the Marlin hits the paper, you know it. There's a big gaping mouth of a hole where the lead made its entrance. Expansion is immediate and violent. The .30-06 bullets on the other hand, delay their expansion. After firing the Hornady 165, I was halfway from the shooting table to the penetration test crate before I could confirm that I did actually hit the paper, the entrance hole was so small. Which expansion type is more preferable? I don't know. What we can do though, is calculate a theoretical wound volume based on expanded bullet diameter times the depth of penetration. Using this figure of merit, the super expanding, but relatively shallow penetrating .444 loads come out head and shoulders as the top performers. If we were talking about deer at modest ranges, I don't think you could find a more devastating round in any caliber. But if we're talking about elk hunting, and we are, depth of penetration requires a little more weighting in our selection criteria than wound volume. Elk are heavy of bone, and nothing in this test simulated the effect of smashing through bone on the way through the animal. I would expect that the Nosler Partition would be the best performer of the seven, taking bone into consideration. The big question with the Nosler is this: After initially blowing off its nose capsule, is its essentially unexpanded diameter big enough to do the job? It just may be. So for the time being the answer for me is to load my rifle with one Hornady 265, one Nosler 250. One Hornady 265, one Nosler 250 . . . Or would you do it the other way around? I've got a load for the Hornady that shoots with sufficient accuracy for me. The only job left is to experiment with the Nosler, to find a load which shoots as accurately, and provides a similar point of impact. © Honeywell Sportsman Club. All rights reserved. | |||||||||

The Honeywell Sportsman Club is a small group of shooting and outdoor enthusiasts in the

Phoenix, Arizona area. Our website is ad-free and completely free to use for everyone.

But we do have expenses that we need to cover, such as the web hosting fee and our liability

insurance. If you enjoyed visiting our website, found it useful in some way, or if you enjoyed

reading this story, please consider tipping us through our PayPal donation jar below. Thanks for visiting, and come back soon.

![]()

Articles

Docs

Eqpt

Events

Join

Links

Misc

New

Pix

Targets