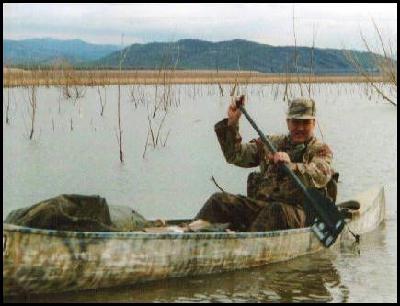

| The Great American Canoe | October 1995 | ||

| Gerhard Schroeder

| |||

For reasons I've never quite completely analyzed, I'm pretty much fascinated about waterfowl hunting. For many years, my tactics were limited to what could be stalked from the bank and retrieved using waders. I began checking out canoes, in catalogs and at REI, and was jerked back to reality through sticker shock. So I turned to the local classified's. Eventually, I found a 14 footer advertised for $160. It turned out to be a 15 footer, home-made (or so the title says), of fiberglass construction. Light, and in my mind, a class above a Coleman. Virtually a one-man craft, but enough to test out the canoe concept.

Putting in at the cove just south of the ramp, paddling was easy and progress was swift. Well, stupid me, that was due to a slight wind from shore. Once out of the cove, and away from the cover on shore, the wind was stronger; in fact, a storm was approaching. I decided to turn around. But the wind didn't let me! As hard (and by now frantically, panic driven) as I could paddle, the wind always straightened the canoe back out, and aimed me back out into the lake. I finally realized that all I could accomplish was to aim for a steep shore about half way to the dam. Once I got there, I jumped out and pulled the canoe, while stepping from submerged boulder to boulder. I did made it back, after dark and totally exhausted. Lessons learned: buy a big paddle and learn the appropriate strokes to maneuver the canoe. Even with a large paddle, another pain is currents. Paddling upstream is murder. Providing that the flow is low enough that you make progress in the first place, canoeing upstream will fatigue you in short order. Last season, Dan Martinez and Steve Garbrecht in Dan's Old Town and me in my "custom" met at Horseshoe Lake, or what was left of it at 8% capacity. With no action on the main water, we decided to head up the Verde. Didn't get very far once we faced the Verde's current. In fact, when we realized that near the banks the ground was firm, we stepped out of the canoes and pulled them upstream. Gave my shotgun a solid bath in the process when it slipped off my shoulder while towing the canoe up river. All in a good day's worth of fowl hunting. Oh, the days combined bag? One merganser, with all three of us emptying our barrels, from both banks, as he came in. Back to the waves. Got another unscheduled taste of those during an earlier waterfowl hunt at Horseshoe Lake. By now my outfit had been upgraded with a trolling motor (which, in case you wonder, doesn't have enough power to get the canoe upstream, because we tried that without success). The electric motor got me in comfort to the upper end of the lake, first thing in the morning, with the water as flat as a mirror. I had set up some decoys and bagged 3 ducks when around noon, the wind came up and turned the lake into a boiling pot of whitecaps. That improved hunting, and I soon had my last duck. Instead of waiting for the wind to stop (who knows how long that would take) I decided to stay close to shore and head back. With the trolling motor at its highest setting in order to make progress, the paddle was used to stabilize the direction, a full-time job for sure. The tip of the canoe would get lifted out of the water by the waves up about two feet, and then smacked back onto the next. At first this was quite exciting, but I soon realized that in spite of all the commotion, the craft was barely making headway. I made it back most of the way, when David Stimens came over in an inflatable powered by a 7.5 HP gas motor and towed me back to the truck. David wanted to fish that day, but he caught nothing but waves. Since then, I have even repeated this rough water stuff in the dark, at 5:30 in the morning, to get to a good duck stand. Like I said earlier, I like to hunt ducks, and if I've already driven all the way to the lake, I might as well hunt. So I brave the waves. To figure out what my options might be should I push the envelope a little too far and get a wet ass because I flip the damn thing, I took the canoe to Canyon Lake two summers ago and purposely rolled it. This was enlightening for me, but plain fun for my son, Joshua. Here are the results: The canoe floats due to two built-in air chambers. In fact, when it floats upside down , you can breathe from the air pocket created by its hull. With Joshua and me in it he could not make it roll. I told him to try as hard as possible, with me correcting, using only the paddle. He couldn't. Once rolled, I could flip it back over (right side up) while swimming in deep water. Joshua could climb back in using the "enter from the end" technique, but my lard ass could not - the canoe would sink! All this was with an empty canoe, and dressed in swim trunks only. During hunting season, wearing a thick layer of clothing, topped off with waders, it would therefore be best to just swim to the nearest shore, if possible, with the canoe in tow. Then apply basic survival techniques. Build a nice fire, dry my hide, and put on dry clothes. I usually carry a sealed five gallon bucket containing matches, propane torch, space blanket and some clothes. Hope I'll never have to use them for that purpose. However, I do use the torch regularly to singe off the small feathers that are left after plucking the ducks. Works great on turkeys, too. The sweater comes in handy when I'm at my duck stand early in the morning, where I no longer have to paddle. While hunting I found out early that shooting from the canoe is best while in the kneeling position. I shot at a dove once sitting down, firing broadside and almost took an unscheduled bath, at least got that sobering sensation and for a second didn't know what to do. While kneeling, balancing works best. That is also the position I assume when chasing crippled ducks. Once within range, they will dive. That's when I grab the shotgun so I'm ready to fire when they re-surface. In the kneeling position I can swing the barrels through a wider arc. Hunting from the canoe doesn't seem to work. Shooting directions are limited, plus the ducks notice the craft and stay out of range. I use the canoe to get to a decent place on shore. There, I can wait in comfort, while the canoe is hidden near by, but instantly ready for chasing potential cripples. Works great! Come to think of it, can't wait for next duck season. And, yes, the canoe is a keeper. © Honeywell Sportsman Club. All rights reserved. | |||

| If you enjoyed this story, or found it useful, please consider clicking here to join the NRA at a discount of $15 off the normal membership cost. You will be supporting both this website and adding your voice in support of the Second Amendment. Thank you very much. |

|

|

|