| Articles | Documents | Equipment | Events | Links | Membership | Miscellaneous | Scrapbook | Targets | What's New |

| Spring 1996 Turkey Hunt: Lessons Learned | May 1996 | ||||||||||

| Dan Martinez

| |||||||||||

We spent a full week in the woods, and what was most remarkable about this trip for me, was that we learned at least one new lesson in Arizona turkey hunting each day we were out there. Dave had just bought a new Mini-14 (caliber .223 Remington) for this trip, and I was sporting my faithful, but so far unlucky, Savage M24 in .223 over 12 gauge. There were early signs that this trip was going to be a good one. As we drove in, about 4 to 5 miles from the chosen hunting spot, we spotted a turkey sauntering up a hill. We jumped out, Dave dug around behind the pickupís seat for the Ruger, and gave chase. The turkey eluded him, but it was a good sign nonetheless. We got to the camp spot, and in about an hour, had camp thrown together. There was still about 45 minutes of light left, and I wanted to show Dave my secret turkey spring. Iíve visited this spot on about ten different trips (some during turkey season, some not) since I discovered it about 4 years ago, and there is always turkey scat there. As we approached the open area from the woods, Dave saw movement. At first he thought it was a skunk, but then we realized it was a pair of hens! This was gonna be a good trip! We ended up scaring off the hens, and I hurriedly put up some blind material between a couple of trees overlooking the clearing, before we lost the light. The next day, we got there around first light, set up a hen decoy in the clearing and sat down to wait. For this trip, Dave picked up a slate call and I had a push-pin box call and a mouth diaphragm. Dave also picked up a diaphragm, and practiced on the drive up. He got discouraged when he realized that the only thing he could do with that mouth call was spit all over me, so, since he wanted me to show him where the birds were, he put it away for the rest of the trip. He was doing pretty good with that slate, however. Slate calls are very good for making close-in purrs and clucks, and he was getting those sounds down. Where we set up at the spring, Dave was to my left, covering the lower half of the slope, and I was covering the upper half. I could barely make out Daveís shape through some foliage. So we were sitting there, alternately making sounds on our respective noise-makers, when suddenly, I sensed some frenzied motions coming from Daveís position. I looked over and saw him shoulder the Mini-14, and a second later, shoot. He didnít get up, and I didnít want to say anything, not knowing what was going on. About a minute later, "Did you see him?" "Uh, no Dave. What happened?" Turns out, our calling, and the rubber hen, had lured in a coyote. As Dave tells it, the coyote was in a full-bore run, set to pounce on the decoy. When it got close, Dave had to extricate himself from some blind netting before he could raise his carbine. At that point, the coyote put out full flaps to slow down and reverse course. Dave didnít get the shot off until after the dog was heading back in the direction he had come. The shot didnít connect. We did have a couple of hens walk in on us a couple of times, later in the morning, but we never did hear a gobble that morning. We headed back to camp for lunch, and hung around the spring for the rest of the afternoon, but saw no further action. When I got up the next morning at 4:15, I heard Dave mutter from under his sleeping bag, "Iím not going to hold you up this morning." It had frozen overnight the first two nights of our trip, and I couldnít blame Dave for not wanting to get out of his warm bag. I would learn later that Dave was a bit under the weather. His sinuses were acting up, and the altitude was not helping his breathing either. This morning was much of the same, but no coyote. A couple of hens came bopping by, but no toms. Again, I didnít hear any gobbling, which was of some concern. Sitting there in the blind, the no-luck blues really started to hit me. I started thinking about what a stupid thing this turkey hunting was. Why the hell was I busting my balls, getting up out of a warm sleeping bag, at 0-dark-thirty? Then, sitting around, looking at the same old trees, hour after hour, hoping that a large, but scrawny bird would happen by. Compared to a deer, itís not that much meat either, to be investing in all this equipment, and all this time. Well, this was what I came here for, so I might as well give it my best. At around 9:30, I got a little bored and built a new blind. I was rolling a stump, to be used for a seat, towards the new blind, when I heard two shots on the plateau up-slope from me. "Hmmm. Dave must be playing with the squirrels again," I thought to myself. I finished the morning in my new blind, and headed back towards camp around 11:30. As I approached camp, I met Dave and he was bubbling over. "Come on Dan, you can help me find my bird." Dave told me a story about how he finally rolled out of bed around 7:00, and not wanting to walk in on me down at the spring, stayed on the upper plateau. At about the time I was building my blind down below, he was talking turkey to a tom. The bird had crested a rise on an old logging road, at a range of about 40 yards from Dave. Dave took the shot, and the bird started thrashing. At just about the time Dave started to slap himself on the back, the bird regained his composure, and raced off through the woods. Dave got off a second shot through a hole in the foliage at a range of about 65 yards, but the bird kept going. Dave had spent the intervening time looking for the bird, and when I rejoined him, we spent about another hour. We did find some feathers where the bird was when Dave took his second shot, but no bird.

I had made up some "dum-dums" by sawing off the tips of FMJs for use in my combo gun rifle barrel, but these wouldnít feed in Daveís semiauto, so he was using FMJís. Daveís theory was that the FMJs merely "cauterized" the wound as they went through.

We decided not to hunt the afternoon, and instead headed to Big Lake to catch dinner. I caught one 11" brook trout trolling, and Dave caught four 10" stockers on eggs. Not only was he out-hunting me, now he was out-fishing me! The next morning, I slipped out of camp leaving Dave behind again. I decided not to head directly down to the spring this morning. With Daveís luck on the top of the plateau yesterday, I decided to hang around on the top, near the edge of the slope, keeping my options open. As the morningís light gathered, I heard a distant gobble to my left, on the slope itself, and started to work my way towards it. The diaphragm call has one thing going for it: volume. The gobble was about a third of a mile off. About every other cackle I would make with the diaphragm, I would receive an answering gobble. I continued making my way toward the sound. I stopped often, taking up a hide, hoping that at some point, the bird would start getting louder, indicating that he was coming in to me. But at each stop, the volume of his gobble stayed constant. Finally, I got to a position where I was able to discern some movement, about 150 yards away, through the heavy forest growth. I closed in another 50 yards, and was relieved to receive another answering gobble. Then I saw it! I was in deep, dark shadow, but 100 yards off to the east, through a hole in the foliage, was a turkey fan, backlit by the rising sun! It stayed in position for about 10 seconds, and in the days since, Iíve wondered whether I should have tried a shot at such an obvious bullseye. I didnít. I called a few more times and got an answer, but he still wasnít coming in to me. A few minutes later, I learned the reason why. Through yet another hole in the foliage, I could see the sunny slope the birds were on. Then the clear silhouette of a hen turkey walked into, then out of the viewport. Next, a second hen turkey silhouette paraded across the window. Finally, the silhouette of a tom turkey in full strut, followed the two hens. The bird was all puffed up, fan in the air, looking just like all those turkey caricatures you see around Thanksgiving time. Two hens in hand beats one in the bush anytime. A few minutes later, I heard his last gobble of the morning. It was 7:05. Around 7:30, I decided to move the rest of the way in, but when I got there, the birds were gone. I found a couple of feathers, and a bare sunny slope with a lot of scratchings. I took up another hide in shadows, with a good view of the sunny slope, in the hope that the tom might come back around 9:30 or 10:00 looking for that other hen he was talking with (me). This gave me some time to ponder some more lessons learned:

Now, if youíve read any turkey hunting literature at all, one of the cardinal rules is never to stalk in on a gobbler. Well, this probably makes a lot of sense back in the populated East and Midwest, but I donít believe the rule has much merit here in sparsely populated Arizona. The rule is made to avoid the situation of two hunters stalking in to the same gobbler from different directions and shooting each other. In my little patch of turkey woods, as many times as Iíve hunted there, Iíve never once run into a hunter from another party. Now suppose there was another hunter there. Real hens simply donít call to a tom as stridently, and as often as a hunter trying to locate a tom. If I heard another hen loudly yelping, often, I would immediately abort the stalk, assuming another hunter. There was one time, when we did hear a real hen yelp nearby once, and it gave us pause. Was that another hunter? I can only hope another hunter would do the same, upon hearing my loud and strident yelps, and would not continue to stalk in silently.

It took a while for us to realize what we were seeing. Those bare patches were all over the place, but only when I saw the birds, and the bare churned ground together, did the now obvious association occur.

Though, thereís still a chance for that 10:00 gobbler. He never did come back. I even set out the rubber hen for him, too. Oh well.

I talked over my experiences and conclusions of the morning with Dave when I met up with him at lunch time. He agreed with me, at least in principle. We formulated a plan to do exactly that, hunt the gobble, the next morning. We headed to town to pick up some softpoints for Dave, then tried our luck at Lee Valley Lake for the afternoon (no luck). Sunrise the next morning found us together at the top of the slope near where Dave cauterized his bird two days ago. Right on plan, we heard a distant gobble to our right, toward the spring. The hunt was on! I cackled on the diaphragm and got an answer. We started down the slope towards the sound of the bird. Like the previous day, we stopped a number of times and called in place to try to coax the bird in to us. But each time we stopped, the bird gobbled from only one place. We eventually found ourselves at my last blind at the secret turkey spring. The sound was coming from across the clearing, in the woods up a slope on the opposite side. Dave and I took up the hide and called for about 10 minutes. He was talking to us, but still he wouldnít come. "All right Dave, thatís it. Iím going in." Dave was still convinced that if we just called a little longer he would come, but I knew he wouldnít. I crossed the clearing, skirting the trees at the edge. The bird was just over the rise in front of me. I turned to look towards Dave, and it turns out he had decided to join me. We had a short conference at the base of the hill. At this close range, the diaphragm would be too loud. I agreed to put it away, in favor of Daveís soft purring on his slate. We started up the hill. About half way up the hill, Dave purred on his slate. The answering gobble was immediate and loud. This was it! He was finally coming toward us! We scrambled for concealment. I flicked the barrel selector of my combo to shotgun as I crouched behind a bush to the left of a large ponderosa. Dave continued purring from behind the big pine. The tom gobbled again. I shouldered the Savage, but it became apparent that I was in a bad position. The tom would have to be as close as 10 yards before I could see him because of the rise of the land, and the low bushes in front of me. Dave slowly stood up behind the concealment of the tree trunk. "Dan, I can see him!" The bird was still thirty yards out, and through a small hole in the dense foliage, Dave saw the bird emerge from behind a downed log, from beard to top of head. "Dan, I got him!" I could do nothing from my position. Hearing no protests from me, Dave took the shot! It was 5:55 a.m. We both scrambled out from behind the tree to meet the bird. I raced past Dave and saw a bird running to the right up a slope. "Dave, heís running, heís running!" "I got him, Dan, I got him!" The bird turned, ran back down the slope, and with the whooping of huge wings, took off into the air. "There he goes, Dave!" I was just about to swing on the bird as if it were a giant flushing quail, when Dave said, "No Dan, look!" and pointed to a thrashing bird on the ground.

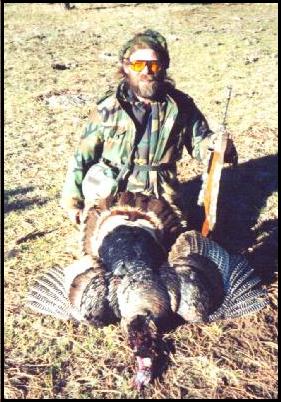

Apparently the healthy bird was a hen that the gobbler already had with him. I walked over to Dave to admire the tom. This was the first wild tom I had ever seen up close and personal. This bird was big! The .22 caliber pill struck him in the neck, half way between body and head, tearing the neck open for about 8 inches of length, and had broken the spine in at least one place. Somehow, he was able to make one last desperate attempt at escape as he flapped around in the forest duff, carving out a turkey shaped "duff angel." And then it was over. Vigorous high fives and backslapping ensued as we hefted the bird and admired the spread of his wings and the irridescence of his feathers. Back at camp, we measured the beard at 8 inches, and the spurs at ĺ inches. The plan we had cooked up the day before, executed exactly to script! We knew how to get our bird now! With two more days left, we felt confident that a second bird was also as good as in the bag. But as Gerhard says, thereís a reason that itís called hunting, and not shooting. The next day was met with great anticipation. We went to the edge of the slope and as the sky lightened, and the tweety birds started singing, I let loose with some loud cackles. No answer. We cackled there for about 10 minutes, without encouragement, then decided to move downslope. I continued cackling as we moved. No answer. Things were looking grim. The later it got without hearing gobbles, the more our chances evaporated. We ended up traveling about a mile and a half with not a single gobble before we ended up back at camp around 8:00. The dayís hunt was over. The great plan had one great flaw: to hunt the gobble, youíve got to have a gobble to hunt. We decided to stay out of that neck of the woods for the rest of the day, to give the area a chance to calm down. We had done a whole lotta hootiní and a-holleriní the day before, so there was reason enough for the area to be dry the next day. I almost decided to cut the hunt short by one day and head home, but in the end, decided to try one more morning. We goofed off for the rest of the day -- went to meet the stocking truck at Sheepís Crossing on the Little Colorado. We half-heartedly fished for the new plants, but they were still in shock, and were not too enthusiastic for the morsels we presented. I dragged myself out of the bag in the dark one more time, and headed for the edge of the slope. We waited for the tweeties to start singing, then cackled. A gobble! Or two! Both were in the same general direction, and we started to move. Something was different this time, though. On the previous two days, the gobble rate (ratio of answering gobbles to our calls) was 50% or better. Now it was down to about 10%. The birds were being a lot more close-mouthed and wary. We tried to follow the gobbles as best we could, but without enthusiastic gobbles to guide us, it was difficult to know where to move, how fast. We heard the last gobble at only 6:00 a.m. I was led to theorize:

Once again I came home birdless, but that I was able to help another hunter get his quarry is always success in my book. And look at all the new knowledge I picked up! Itís trips like this one that create great anticipation for the next one. © Honeywell Sportsman Club. All rights reserved. | |||||||||||

| If you enjoyed this story, or found it useful, please consider clicking here to join the NRA at a discount of $15 off the normal membership cost. You will be supporting both this website and adding your voice in support of the Second Amendment. Thank you very much. |

|

|

|